There’s an excellent article on the highs and increasing lows of the synthetic marijuana ‘legal high’ industry in the Broward Palm Beach New Times.

There’s an excellent article on the highs and increasing lows of the synthetic marijuana ‘legal high’ industry in the Broward Palm Beach New Times.

The piece is an in-depth account of how a legal high company called Mr. Nice Guy became the biggest fake pot manufacturer in the US.

It describes in detail how the business created and sold the product – only to fall foul of the rush ban on the first wave of synthetic cannabinoids.

The company was eventually raided by the Drugs Enforcement Agency and is waiting for the case to be tried in court. However, it’s still not clear whether they actually broke the law.

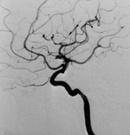

They changed their formula a few months before the raid to use two cannabinoids, called UR-144 and 5-fluoro-ur-144, which are not specifically covered by the current ban, so the prosecutors have to argue that they are close enough to the prohibited molecules to be illegal.

A curious point not mentioned in the article is that cannabinoid 5-fluoro-ur-144, also known as XLR-11, had never previously been described in the scientific literature and was first detected in synthetic marijuana.

It is listed by companies that sell research chemicals (for example, here) so you can buy it straight from the commercials labs.

But the data sheet makes it clear that structurally it is “expected to be a cannabinoid” but actually, it has never been tested – nothing is known about its effects or toxicity.

Previously, grey-market labs were picking out legal chemicals confirmed to be cannabinoids from the scientific literature and synthesizing them to sell to legal high manufacturers.

But now, they are pioneering their own molecules, based on nothing but an educated guess on how they might affect the brain, for the next wave of legislation-dodging drugs.

Fake pot smokers are now first-line drug testers for these completely new compounds.

Link to ‘The Fake-Pot Industry Is Coming Down From a Three-Year High’.

A curious

A curious

The brilliant, infuriating, persistent, renegade psychiatrist

The brilliant, infuriating, persistent, renegade psychiatrist  i-D magazine has an

i-D magazine has an

A documentary on the trauma of war, banned by the US government for more than 30 years, has found its way onto YouTube as a freely viewable

A documentary on the trauma of war, banned by the US government for more than 30 years, has found its way onto YouTube as a freely viewable

The Observer has an

The Observer has an

An amazing description of how sociologists who wanted to do field studies in Belfast during the height of

An amazing description of how sociologists who wanted to do field studies in Belfast during the height of  In a

In a