One of the things I quickly discovered while working for Médecins Sans Frontières in Colombia, was that while there is lots of research on people who have experienced armed conflict in the past, there was very little information on the mental health of people living in active conflict zones.

One of the things I quickly discovered while working for Médecins Sans Frontières in Colombia, was that while there is lots of research on people who have experienced armed conflict in the past, there was very little information on the mental health of people living in active conflict zones.

With MSF colleagues, we’ve just published a study that goes a little way to correcting that.

The majority of research on how war effects civilians is done on refugees or in post-conflict situations. Practically, this makes sense, as collecting data during an armed conflict can be both difficult and dangerous.

However, MSF in Colombia runs almost all its clinics in exactly this situation. The fact there was little research on which to base our interventions made my job a little challenging at times, but as we were also collecting systematic data on each consultation this also gave us a great deal of internal information on which to base decisions.

During my time there, we set ourselves the task of analysing and publishing some of this data to make sure others could benefit from it. This study has just appeared in the journal Conflict and Health.

The study looked at how symptoms of mental illness were related to experience of direct conflict-related violence (exposure to explosives, threats from armed groups, deaths of loved ones etc), violence not directly related to the conflict (domestic violence, child abuse etc) and what we called ‘general hardships’ – such as economic problems and poor social support.

We predicted that the more someone was exposed to violence from the armed conflict, the worse mental health they would have, but what we found was a little different.

Experience of the armed conflict was more linked to anxiety while non-conflict violence was more related to aggression and substance abuse. Depression and suicide risk, however, were represented equally across all of the categories.

This is interesting because a lot of conflict-related mental health interventions are focused on trauma and PTSD, where as our study and various others have found that trauma is only one effect of being caught up in an armed conflict.

It’s worth saying that being ‘trauma obsessed’ is really just a American and European condition – as I’ve discussed before, Latin American psychology in particular has a strong tradition of looking at problems on the community level rather than always aiming to treat the individual victims.

It’s worth saying that the study used clinical data, rather than data from a specifically designed study, so there is still a need for a systematic approach to the problem. But as study of over 6,000 patients who were seen in areas of active conflict, we hope it’s a useful contribution.

By the way, MSF’s work continues in Colombia. Everyday there are medical and mental health teams spending days, weeks or months in conflict zones to work with the local population who would otherwise have no access to healthcare. In over 60 countries around the world the organisation does something similar in very difficult conditions.

They also do lots of important research particularly into medical problems that often get neglected.

The majority of the staff are from the local country and they invest a lot into training.

Do drop them a donation if you get the chance.

Link to MSF Colombia study on the armed conflict and mental health.

One of the things I quickly discovered while working for Médecins Sans Frontières in Colombia, was that while there is lots of research on people who have experienced armed conflict in the past, there was very little information on the mental health of people living in active conflict zones.

One of the things I quickly discovered while working for Médecins Sans Frontières in Colombia, was that while there is lots of research on people who have experienced armed conflict in the past, there was very little information on the mental health of people living in active conflict zones.

At some point, one of the two circles would fill with randomly oriented stripes for just 50ms (one twentieth of a second) and afterwards the participants were asked to say which direction the stripes were pointing in.

At some point, one of the two circles would fill with randomly oriented stripes for just 50ms (one twentieth of a second) and afterwards the participants were asked to say which direction the stripes were pointing in.

A patient who could only say the word ‘tan’ after suffering brain damage became one of the most important cases in the history of neuroscience. But the identity of the famously monosyllabic man has only just been revealed.

A patient who could only say the word ‘tan’ after suffering brain damage became one of the most important cases in the history of neuroscience. But the identity of the famously monosyllabic man has only just been revealed. A fascinating

A fascinating

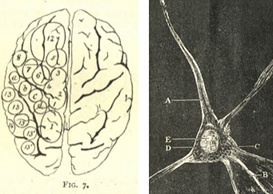

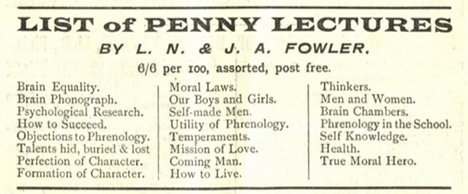

The images on the right are from the June 1890 edition (the brain) and October 1895 edition (the neuron) and both show some of the then cutting-edge neuroscience that the magazine regularly featured.

The images on the right are from the June 1890 edition (the brain) and October 1895 edition (the neuron) and both show some of the then cutting-edge neuroscience that the magazine regularly featured.

The New Yorker has an amazing

The New Yorker has an amazing

Nobel-prize winning neuroscientist

Nobel-prize winning neuroscientist  The research on the psychological impact of video games tells quite a different story from the stories we get from interest groups and the media. I look at what we know in an

The research on the psychological impact of video games tells quite a different story from the stories we get from interest groups and the media. I look at what we know in an