Last February, a file from the Edward Snowden leaks was released from a 2012 GCHQ presentation called ‘The Art of Deception: Training for Online Covert Operations’. It describes the ‘Online Covert Action Accreditation’ course which draws heavily on the psychology of influence and persuasion. This post will look at how they’re piecing together the science that forms the basis for these online operations.

The work seems to have been put together by GCHQ’s Human Science Operations Cell which presumably exists as an internal consultancy to allow the relevant cognitive and social sciences to be applied to practical covert operations.

One of the early slides lists the subjects the HSOC draws on which stretch from psychology to political science to neuroscience. At the current time, neuroscience has nothing practical to contribute, so they’re clearly blowing their neurological trumpets to sound a bit more high-tech but it’s worth noting the breadth of disciplines they draw on meaning they’ve got a wide and comprehensive vision of human behaviour from the micro to the macro.

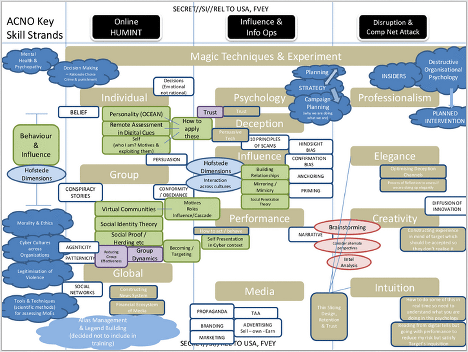

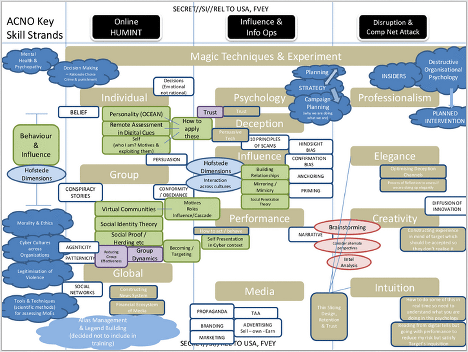

However, one of the key slides has a road map of how everything fits together. It’s shown below and it’s quite dense so you can click the image below if you want a larger version.

One of the first thing that stands out is the ad-hoc-ness of their approach. They’ve appropriated a patchwork of relevant theories as a guide to practice with nothing being drawn from their own data.

You can see the main areas they’re drawing from – which includes profiling cultures and personality, research on persuasion, cognitive biases and scams, research on the psychology of stage magic, and organisational psychology or management science more generally.

Perhaps the weakest elements here are the cultural and personality profiling using Hofstede’s cultural dimensions and a Big Five personality traits. The trouble is that while these are statistically reliable on the group level they predict very little on the individual level because the effects are swamped by individual variation.

This means it may be more useful in the domain of PSYOPS, which attempts to influence groups, rather than targeting individuals.

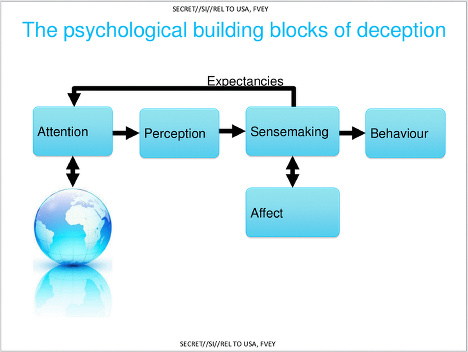

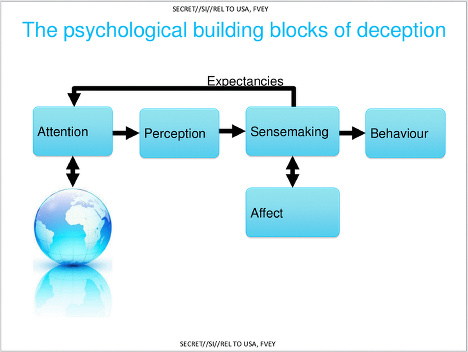

The slide below details the general psychological framework for deception. As far as I can tell, this is the only original piece of psychological theory in the presentation.

It’s more a useful way of organising different approaches to deception rather than a theory in itself. It’s what clinical psychologists would call a ‘formulation’. It’s a way of organising evidence-based effects that may not be thoroughly tested itself but works well enough to aid understanding.

Perhaps the key thing to note is the sensemaking component. Sensemaking is a key concept in management science that just describes the different ways in which people come to conclusions about the meaning and significance of things.

It should be a well-known concept in intelligence circles because it is used both in military people management and military intelligence analysis. Interestingly, they treat individuals as like naive intelligence analysts who are trying to piece together their own understanding of the world and aim to exploit some of the weaknesses in this process. The big messy ‘concept map’ slides mentions ‘destructive organisational psychology’ which presumably refers to using the understanding of what keeps organisation together to break them apart.

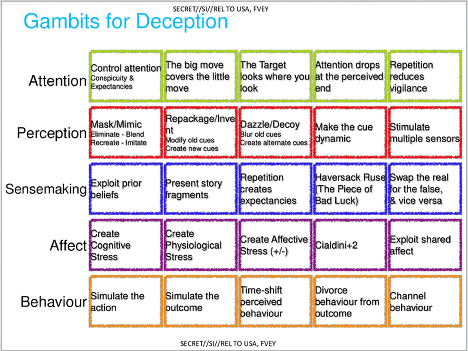

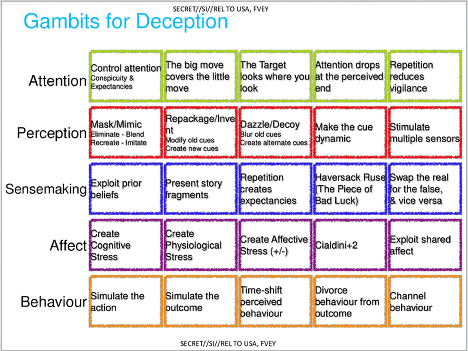

However, in terms of the psychological science which underlies their approach, the next slide is key.

You can see several influences here. The techniques listed under ‘attention’ are all taken from research on the psychology of magic tricks, particularly from Susana Martinez-Conde’s work on how sleight-of-hand artists manipulate attention. Most of it is reviewed in a paper she wrote with a series of co-authors including pickpocket Apollo Robbins.

The HSOC spooks clearly love the idea of the psychology of magic and they refer to it a lot in their presentation. One slide just says ‘We want to build Cyber Magicians’, but it’s really not clear how it applies online. The whole point of sleight-of-hand is that it is dynamic and takes advantage of how you pay attention. When online, however, users’ attention doesn’t necessary flow in a predictable pattern because you can wander off from the screen, pause, grab screenshots and so on. In other words, individuals have better control over the flow of information because online interaction is designed for information control and therefore partial staggered attention.

The ‘perception’ techniques listed on the slide are largely taken from Stefano Grazioli and Sirkka Jarvenpaa’s classic paper [pdf] on online deception entitled ‘Deceived: Under Target Online’. The paper looks at how internet scammers rip people off and assuming that successful online con artists have found useful techniques by natural selection, HSOC just borrow them.

The techniques to exploit sensemaking are largely based on theories of sensemaking itself although the story fragments components seems to be drawn from research on relational agents that are designed ‘to form long-term, social-emotional relationships with their users’. Rather than actually deploying autonomous relational agents, I suspect it’s simply a case of using research insights from the area that suggests, for example, that presenting fragments of the agent’s backstory and letting the other person piece them together makes the person seem more believable.

The techniques in the ‘affect’ section are some general points taken from a vast experimental literature on the psychology of marketing and persuasion that describes how emotion modulates the heuristics (judgement processes) involved in persuasion.

The ‘behaviour’ section is the only part I don’t recognise as coming from the psychological literature. This makes me suspect it comes from PSYOPS or IO practice, but if you recognise it, leave a comment below.

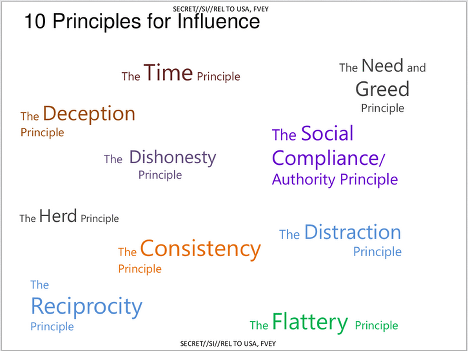

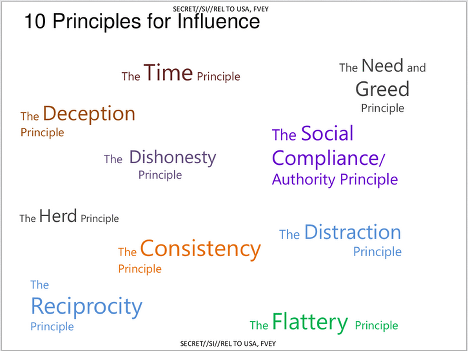

The ’10 Principles of Influence’ is perhaps one of the most interesting slides in terms of illustrating the empirical basis for their approach as they use research both on the strategies of honest persuasion and dishonest scammers.

‘Principles are influence’ are largely associated with the work of consumer psychologist Robert Cialdini but the list actually consists of three of his six principles (Reciprocity, Social Compliance / Authority, Consistency).

Another six are taken from Stajano and Wilson’s classic study ‘Understanding scam victims: seven principles for systems security’ which describes six methods used by con artists. One item overlaps with the Cialdini principles and additionally they’ve included flattery (known to be an effective persuasive tool) and time – although it’s not clear whether they’re referring to giving people time and putting people under time pressure.

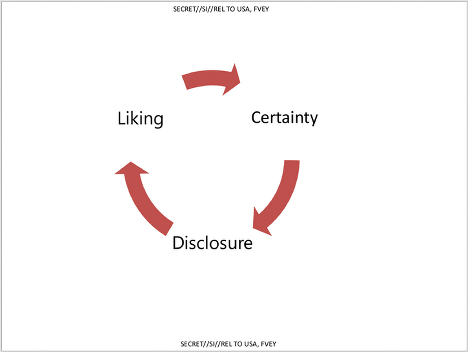

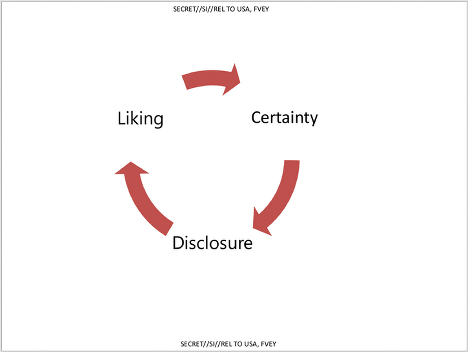

This section seems to be about gaining people’s trust to encourage disclosure and the slide you see above refers to social penetration theory which describes how relationships progress to increased levels of intimate connection through self-disclosure. The slide that follows this gives some basic advice about encouraging this: mirroring communication cues, adjust speech patters and so on – the sort of things you get taught in the first week of a psychotherapy course.

So here’s what the Online Covert Action Accreditation’ course looks like: like a PhD psychologist was given the task to come up with a plausible psychological framework for practical deception and influence online. It draws on a mix of persuasion psychology from marketing, studies on scammers and con-men, the social psychology of trust and disclosure, studies of how stage magic works psychologically, and work on what makes organisations work effectively and what degrades their performance.

This is a comprehensive approach to the problem, but the trouble is, this probably only translates approximately and probably rather poorly into practical effects.

In place of this, HSOC would be better of doing research and lots of it. They could do lots of informal RCTs online and gather a large amount of data quite quickly to test out which techniques actually increase influence or lead to successful deception. What behaviours on the part of the actor lead to increased self-disclosure the quickest? Does a laggy internet connection mean people’s increased frustration affects their evaluation of honest? and so on.

I suspect, however, that the Human Science Operations Cell were, and maybe still are, quite a small outfit and so they’re restricted to a consultancy role which will ultimately limit their effectiveness.

We tend to think that the secret services are super efficient experts with an infinite budget, but they probably just work like any other organisation. HSOC were probably told to deliver an Online Covert Action Accreditation course with few resources and not enough time and came up with the most sensible thing in the time allowed.

Oh, and by the way, hello spooks, and welcome to Mind Hacks.

Link to copy of slides.

Link to coverage from The Intercept.

You’ll get more out of The Skeleton Cupboard, Tanyan Byron’s

You’ll get more out of The Skeleton Cupboard, Tanyan Byron’s  If you’re in London during June, the

If you’re in London during June, the  The BBC is

The BBC is

The BBC News site has a special multimedia

The BBC News site has a special multimedia  BBC Radio 4 has just concluded an excellent three-part

BBC Radio 4 has just concluded an excellent three-part  A fascinating section of the

A fascinating section of the  The latest London Review of Books has an amazing first-person

The latest London Review of Books has an amazing first-person