Over the last few months, the soul searching over the shortcomings of fMRI brain scanning has escaped the backrooms of imaging labs and has hit the mainstream.

Over the last few months, the soul searching over the shortcomings of fMRI brain scanning has escaped the backrooms of imaging labs and has hit the mainstream.

Numerous articles in hard hitting publications have questioned some common assumptions behind the technology, suggesting a backlash against the bright lights of brain scanning is in full swing.

There are two strands to this debate, and both stem from the fact that the technology and conceptual issues of brain imaging are incredibly complex.

To fully understand what happens during a brain imaging experiment you need to be able to grasp quantum physics at one end, to philosophy of mind at the other, while travelling through a sea of statistics, neurophysiology and psychology. Needless to say, very few, if any scientists can do this on their own.

So the first strand involves how brain imaging experiments are reported in the media. Under the sheer weight of conceptual strain, journalists panic, and do this: “Brain’s adventure centre located”.

It’s a story published this morning on the BBC News website based on an interesting fMRI study looking at brain activity associated with participants choosing a novel option in a simple gambling task. But out of the four words of the headline, only the first is accurate.

And this leads to the second strand of the debate, which, until recently, has been largely conducted away from the media’s gaze, amongst the people doing cognitive science themselves.

It starts with this simple question: what is fMRI measuring?

When we talk about imaging experiments, we usually say it measures ‘brain activity’, but you may be surprised to know that no-one’s really sure what this actually means.

Neuroscientist Nikos Logothetis published an important paper in Nature a couple of weeks ago explaining exactly what we know so far about the link between what brain scans measure and what the brain is actually doing.

It’s very wide-ranging and includes lots of grit-your-teeth hardcore neurophysiology, but is, I think, essential reading if you’re neuroscientifically inclined.

It focuses on BOLD, the signal that reflects the ratio of oxygenated and deoxygenated blood measured by fMRI, and the fact that it can be altered by a huge range of different biological process and neural firing patterns.

One of the main points of the paper is that the brain is not simply an array of tiny localised processors, but it is more like an an ecosystem of communication.

Activity can result from sending more signals, trying to send less, or, from what seems to be particularly important – maintaining a balance of excitation and inhibition.

Furthermore, it seems that a great deal of neural activity is not from neurons that might be directly involved in a task, but from ‘neuromodulation’ – general processes of management and coordination, often linked to attention. This can wax and wane, can spread like ripples and can occur in all sorts of non-linear ways that makes interpretation difficult.

What this means is that brain imaging experiments need to be carefully designed to control for these effects, but this entirely depends on our understanding of the effects themselves.

In other words, our understanding of what brain scanning data tells us evolves over time. A study conducted ten years ago might mean something different now.

An article in Science, published in the same week as Logothetis’ paper, reports on new statistical methods for interpreting imaging data, a different issue again.

The latest edition of The New Atlantis has an article that attempts to come to grips with some of the philosophical aspects of brain imaging experiments, in terms of the conceptual limits in inferring mental states from biological changes.

I have to say, it’s a bit miscued in places, assuming that brain imaging relies on ideas about brain modularity (which it doesn’t) and seemingly confusing it with the notion of pure insertion, and suggesting some rather strange notions about mental causation, but it has many good points and is worth a read.

It’s important that these sorts of issues come to light, because it hopefully heralds a time of increased caution in our interpretation of brain scans – and that goes for scientists, the media and the general public.

This is essential, because this data is starting to be used, literally, in life or death decisions.

The same issue of The New Atlantis has an article on neuroimaging that discusses the ethical dilemmas in applying this imperfect technology to legal decisions concerning capital punishment.

Link to Logothetis on ‘What we can do and what we cannot do with fMRI’.

Link to Science article ‘Growing pains for fMRI’.

Link to New Atlantis on ‘The Limits of Neuro-Talk’.

Link to New Atlantis on Neuroimaging and Capital Punishment.

Scientific American has an article on migraines that takes a comprehensive look at the science of this painful and hallucinatory disorder.

Scientific American has an article on migraines that takes a comprehensive look at the science of this painful and hallucinatory disorder. Today’s Nature has an excellent feature

Today’s Nature has an excellent feature  Wired has

Wired has  In 1941, brain specialist

In 1941, brain specialist

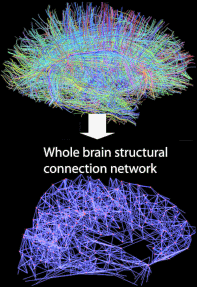

This meant the researchers could identify areas of the cortex that are the most highly connected and highly important, forming a structural core of the human brain.

This meant the researchers could identify areas of the cortex that are the most highly connected and highly important, forming a structural core of the human brain. This week’s ABC Radio National’s All in the Mind

This week’s ABC Radio National’s All in the Mind  A scene from a thousand horror movies,

A scene from a thousand horror movies,  Over the last few months, the soul searching over the shortcomings of fMRI brain scanning has escaped the backrooms of imaging labs and has hit the mainstream.

Over the last few months, the soul searching over the shortcomings of fMRI brain scanning has escaped the backrooms of imaging labs and has hit the mainstream.

New York Magazine has a wonderful

New York Magazine has a wonderful  Magnetic resonance imaging is the most popular method for scanning the brain both for research and for clinical investigations. I’ve just found a wonderfully written

Magnetic resonance imaging is the most popular method for scanning the brain both for research and for clinical investigations. I’ve just found a wonderfully written  In light of research showing that an ingredient in cannabis, cannabidiol, seems to actually reduce the risk of psychosis, I speculated

In light of research showing that an ingredient in cannabis, cannabidiol, seems to actually reduce the risk of psychosis, I speculated  Neurophilosophy has

Neurophilosophy has  What makes a man a genius? Russian neuroscientists were pondering this exactly this question in the early 1900s and did exactly what seemed sensible at the time – they collected and dissected the brains of some of the greatest cultural figures in a huge collection called ‘The Pantheon of Brains’.

What makes a man a genius? Russian neuroscientists were pondering this exactly this question in the early 1900s and did exactly what seemed sensible at the time – they collected and dissected the brains of some of the greatest cultural figures in a huge collection called ‘The Pantheon of Brains’. I’ve just noticed this review

I’ve just noticed this review